Topote de Acahual: Learning the Languages of a Regrown Jungle Through Art, Writing, and Health

In 2020, in the region of Los Tuxtlas, Mexico—an expanse of high evergreen and evergreen tropical forest, defined by volcanic mountain ranges, and rich in diverse, endemic flora and fauna—a series of political-campaign posters began appearing around Veracruz. It was not an election year, and the signs did not promote any of the nation’s mainstream candidates. Instead, they called for “Ojoche para presidente”, Ojoche for President. Ojoche is one of many names for the native tree that produces a nutrient-rich seed by the same name. The posters were part of a 10-day retreat hosted by the tree nursery Vivero de Tebanca, meant to strengthen connections between local people and nature through art.

Topote de Acahual is a collective pedagogical project exploring the multiple languages—ecological, creative, and spoken—of the Los Tuxtlas jungle.

In Tebanca, Veracruz, it is customary for visitors to be welcomed with a Topote taco, Topote being a fish found in Veracruz’ Catemaco Lake. Acahual is the Nahuatl term for the region’s land that is beginning to return to jungle after a period of deforestation. Topote de Acahual, by bringing together collective owners of the land with contemporary artists to craft a new narrative for the jungle, embodies the first fish born from the new jungle.

The project was the brainchild of Esteban Azuela—a digital artist and head of communications for Vivero de Tebanca—and his friend Mauricio Patrón. Also called the jungle linkage program, it aimed to build and express the relationships between the forest and its inhabitants, including people.

The project emerged when Azuela saw a new opportunity to involve himself in the family nursery—a passion project begun by his grandfather Antonio Azuela Rivera and carried on by his father, also Antonio Azuela—that has been critical in preserving seed inventories of indigenous and endemic trees and reforesting areas that had been converted to cattle land in the region. The family had been gathering and logging information on their seed stocks for over 30 years, but Azuela saw a new way to memorialize that information—and engage community members in the process—one that better aligned with his skillset as an artist.

Azuela and Patrón assembled a group of artists from Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico all with different specialties. Aldo Lugo, Ana Emilia Felker, Dan Sánchez D. Vil, Emilia López, Fernanda Barreto, Kweilan Yap, and Melissa Bolaños, joined Azuela and Patrón as “cultural managers” of Topote de Acahual. Because it was during the height of the Coronavirus pandemic, they also invited a doctor who worked in traditional medicine. 20 communal landowners from Veracruz were also invited as participants.

Once the group was formed, they began working collectively to realize Topote de Acahual. They worked to build a framework that linked art and ecology to realign the narratives of flora, fauna, and contemporary society. This included asking questions about opportunities and methods of human-jungle coexistence and the ethical and political choices humans face that influence the ecology of Los Tuxtlas.

Including locals in the project was critical to its mission. Many people around the Los Tuxtlas region have been disconnected from the jungle. The area is a unique ecoregion. As the largest and northernmost intact moist forest in Mexico, it has, historically, been home to robust populations of endemic flora and fauna from vascular plants, reptiles, amphibians, birds, and mammals. But the past several decades have been marked with devastating declines in those populations, with some being driven to extinction.

The worst habitat loss occurred between 1967-1986, during which Los Tuxtlas was being deforested at a rate of 4.3 percent per year. In 1998, the Mexican government established the Los Tuxtlas Biosphere Reserve in response to the area’s biodiversity-loss crisis. But its immediate success tapered off, and a 2018 study showed that at current rates of deforestation, the region protected by the reserve could lose 14 percent of the forest cover that was present in 2011.

Deforestation in Los Tuxtlas has been driven by a variety of human-led causes over the years, but the Azuela family is particularly aware of the role cattle ranching has played, as local people clear their land for more lucrative pastoral purposes. Much of the family’s work through Vivero de Tebanca has been working with local land users to find ways to help trees and cattle coexist on ranchland.

Similarly, Topote de Acahual was, at its heart, a way to bring local people and flora back into touch with each other.

The program’s pitch attracted funding from Fundación Jumex Arte Contemporáneo, the foundation of the Mexico-City-based contemporary art museum, Museo Jumex. With that support, Topote de Acahual was able to bring together the group in person at Vivero de Tebanca for a week and a half of workshops, which the artists took turns leading. They dabbled in print making, creative writing, photography, drawing, embroidery, publishing, and herbalism.

The group took nature walks, during which Azuela said, “we start[ed] listening to the jungle”. Throughout the workshops, plants were the main characters of each creative inquiry. “It was not just gathering information about how to propagate them,” said Azuela. “but also information about, how … our families create relationships with them.” Some of those relationships were emotional and others practical, with many families using native plants in recipes.

The group chose 10 species and created a narrative around each. To stay healthy during the public health crisis framing the world at that moment, they also learned how to use local botanical resources to create kombuchas and other health products.

Eventually, the divide between those invited to be teachers and those recruited as learners began to dissolve, naturally, among the group. Azuela said after a few days, community members started to take initiative to lead workshops as well.

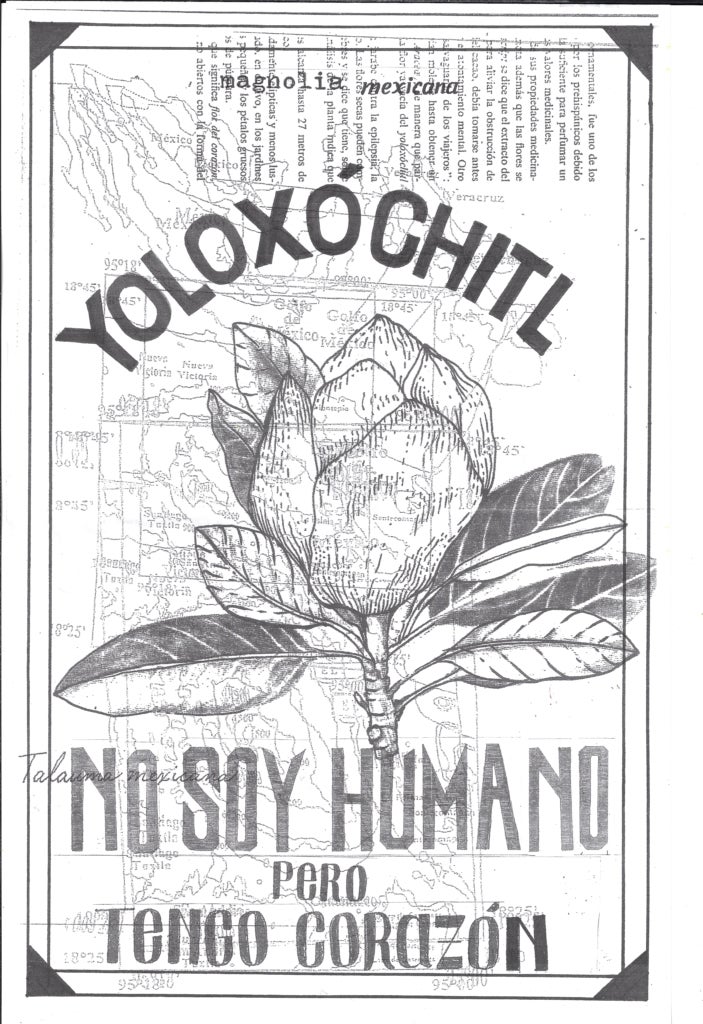

The results of the week were a multitude of art pieces, all telling the story of the jungle through different mediums. Among them were posters, like the Ojoche-for-president design, pasted up around the region using nature-friendly glue; zines compiling photocopies of pieces from various workshops; and collections of photographs, one of which portrays a gallery of participants, a large leaf in place of each model’s face.

“This is a special project for me,” said Azuela, explaining that it came from a place of “love for the life and the community” around Los Tuxtlas.

To date, the Azuela family has not yet been able to assemble a second group, though they hope to eventually. “We would love to have the funds to create this experience again, because everybody—the community, and artists, everybody—was … blown away [by] the things that happened here,” said Azuela.

The family is also exploring other ways to bring artists into the fold. They have space to house guests and hope to use it to begin offering artistic and academic residencies on the nursery grounds. “This is one thing that we want to pursue this year,” said Azuela. “To invite as many people as we can to create louder voices [for them].”

The people who brought Topote de Acahual to life through their participation in the project who were not already named are: Amelia Lucho, Angélica Vargas Salazar, Aureliano Gómez Juan, Brissa Guadalupe Domínguez, David Antonio, Edith Carrera Sánchez, Elias Márquez, Esteban Oltehua, Isidro Belli, Ismael Parada, Jenny Cárdenas, Jocelyn Azeneth, Jorge Luis Sáenz, Lidia Cervantes Calixto, María Espíndola, Maximina Juárez, Mildred Hernández Toto.

Have news? Share updates from your organization or country by emailing lrobinson@lincolninst.edu.