With Pen and Ink, Mattie Rose Templeton Illustrates the Importance of Darkness and the Intricacies of Nature

“Maybe we never would have turned our backs on the night had we not come to define darkness as an absence—as a lack, a deficiency, an aching void calling out to be filled. But that is among our acts of original sin, and so—fiat lux (let there be light).”

— Peter Friedrici, Freelance environmental journalist; Orion Magazine

—

Across the world, 80 percent of people live under light polluted skies; in the United States and Europe, 99 percent do. Communities have come to expect and even take comfort in the ceaseless glow of modernity. But darkness—true untouched darkness—is critical to the health of nature from insects to humans. Maine Artist Mattie Rose Templeton explores the phenomenon and impacts of light pollution in illustrations for the Appalachian Mountain Club’s (AMC) first children’s book, “If You Can See the Dark.” The project is one of many she has done that uniquely captures the beauty—and magic—of the natural world.

“Storytelling with pictures is a powerful thing,” said Templeton. “I believe that, if we can teach children at a young age the importance of conservation and protection of wildlife, it will influence the action they take to protect these things into the future—their future.”

Written by Timothy Mudie and Jenny Ward, “If You Can See the Dark” explains the importance of dark skies for animals, plants, and people, and the way light pollution disrupts their health. The AMC came to Templeton—whose work and style have become well-recognized across New England—asking her to collaborate on the project, which is inspired by AMC’s Maine Woods International Dark Sky Park.

The park stretches more than 14,000 square kilometers (over 5,400 square miles) from Monson, Maine, to the Canadian border. In addition to being one of the darkest places on the East Coast, it fosters a high level of habitat connectivity and climate resilience. The park was awarded certification as a Dark Sky Park by the International Dark-Sky Association in May 2021. The association makes these awards to places that maintain an “exceptional quality of starry nights and a nocturnal environment that is specifically protected for its scientific, natural, educational, and cultural heritage, and/or public enjoyment.”

Templeton said the values instilled through stories like this one can be introduced to children early. “No child is too young to understand concepts like balance and the idea that overuse can lead to resource depletion.” Sharing these ideas with children can be a gift. “We have a lot more knowledge today than our parents did, and we stand at an interesting moment, when it is so vital to start teaching new habits of how we inhabit our Earth.”

Templeton grew up with an intimate understanding of nature and rural living. She was raised in what she called the “breadbasket [and] blueberry fields” of Maine in a home with no electricity. Her family ran their life off solar, wind, and muscle-power. They had a wood stove, gaslight lamps, a composting toilet, and manual water pumps. Today, she has a few more amenities but still lives “off-grid” in a fully solar-powered home.

This has made her appreciate what feel like particularly pure moments in nature. “There’s a quietness to that [lifestyle] that I think you don’t get when you have a bunch of lights and fans and noise,” she said.

As a young child, Templeton was homeschooled and encouraged to spend most of her time outside exploring. “That was the beginning of my appreciation and love for nature,” said Templeton. During this time, her mother noticed and fostered her daughter’s affinity for creating and made sure she had all the tools to explore her artistic interests. These interests included, “everything from painting something to going and building structures out of sticks in the woods.”

Later, when Templeton attended public school for the first time in seventh grade, she struggled with the transition but found solace in the art room where she was given free range of the paint closet. She discovered oils and fell in love with them.

When college crested the horizon, she headed to Sante Fe, New Mexico, beckoned by the promise of the renowned art mecca. But she did not see art as her future. She believed she needed to develop other skills to make a living. So, she pursued nursing, then furniture restoration; she worked as a waitress and as a cook. None of it felt right.

In 2018, she moved back to Maine and signed up for an art show on a whim. Her newest interest was pen and ink and she prepared a collection of illustrations to display. On the day of the show, she sold out.

“It lit a fire in my heart,” she said. For the first time, she thought, “I can do this … I have something to say.”

For a while, she kept working part-time as a chef and selling her art on the side. “I was so scared to let that ‘real-job’ chef job go, when what was really supporting me [already] was the art,” she said. Then the pandemic struck. That “real job” evaporated, but her art was still there. Ever since, it has been her full-time job.

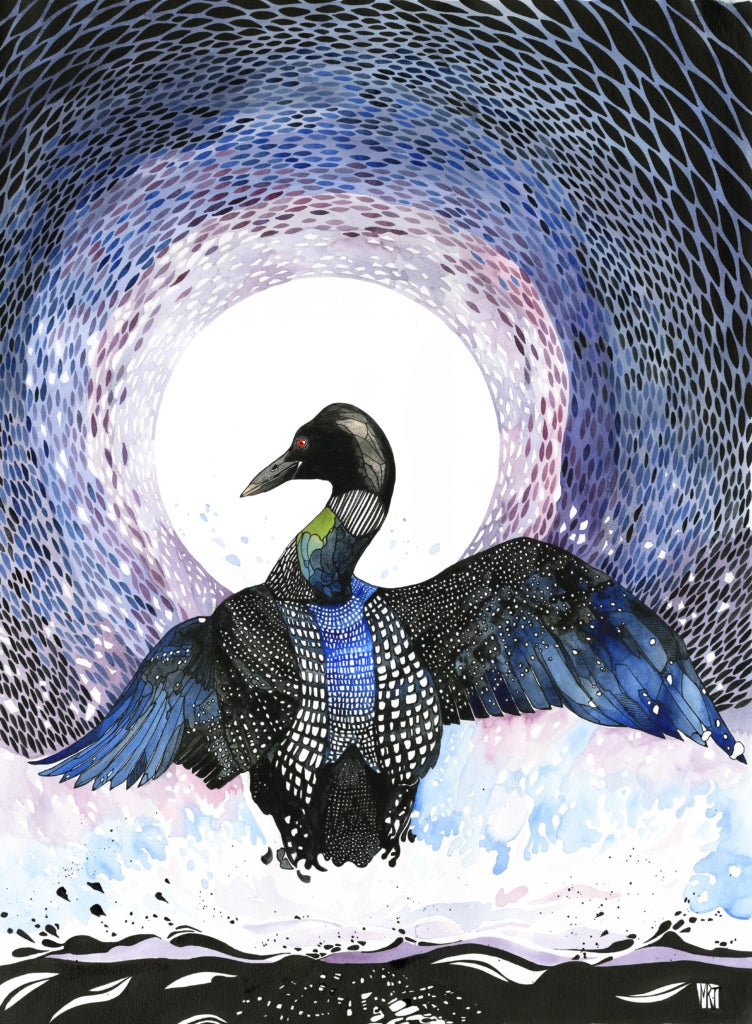

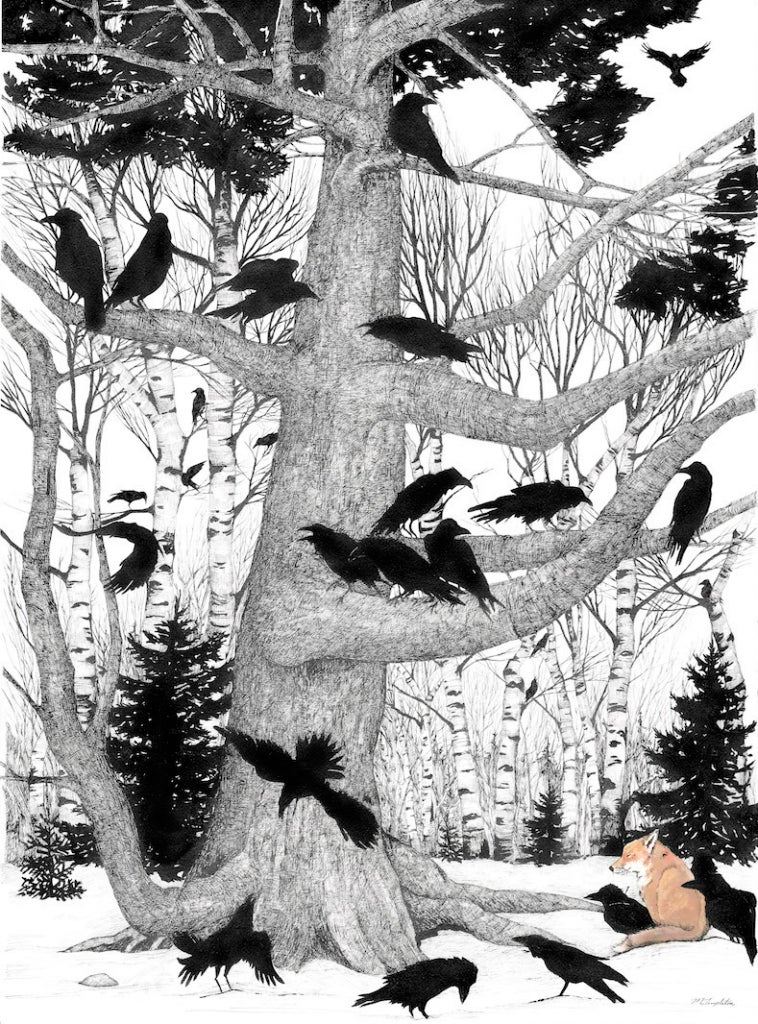

Templeton’s quick success is not surprising. In her illustrations Templeton strikes a mesmerizing balance between realism and the abstract, evoking perfectly the way design and geometry appear naturally in wild places, from the pattern of wind in tall grass, to the veins delicately dividing a leaf. Color, shape, and pattern come together in her work to press pause on the moments, both stunning and mundane, that are so easily blurred by the pace of life.

“I like to dance on this line of things that are real, but they seem like they could be magic. Because I think in nature there is magic,” said Templeton.

But Templeton has no illusions about the fragility of that magic. Living and working in tune with the land and with a partner who works for a land trust, she is acutely aware of the pressures on Maine as both a harbor of some of New England’s wildest places, and a beloved vacation destination.

Recently, she has been heartened to notice the impacts of a burgeoning private land conservation movement. “That always makes me excited when I hear of [projects like] the AMC designating a dark skies area or people donating thousands of acres that they don’t want to see developed,” she said. “My hope for the future is that more people see the value in wild land versus built land.”

She sees a role for art in that journey. “Art is beautiful and there’s nothing wrong with creating beautiful art. But I do want people to think deeper than the beauty of it. The story behind the art is important too. My hope is that people will feel inspired to protect the things that need protecting and if I can influence that through art, then I have done my job.”

More About the Artist

Mattie Rose Templeton is a self- taught artist specializing in pen and ink drawings of the natural world. She uses an “old-fashioned” ink well and different sized nibs to vary texture, lines, and shapes throughout her works, which often take on a conceptual angle. She began working mostly in black and white, but has, more recently, ventured into the world of color. She is now working on a second book, also in collaboration with AMC, which will focus on the issue of water pollution. You can find more of Templeton’s work at mattierose.net and follow her on Instagram @mattierosetempleton. Outside of work, she enjoys playing with her two young children and working the land at her off-grid home in rural Maine.