Water Woman: Marion Stoddart’s Crusade to Save One of America’s Most Polluted Rivers

Lily Robinson – ILCN Program Coordinator

The path along the Nashua River has softened to sandy mud and the wood bridges that span it puddle beneath Marion Stoddart’s boots. The Mine Falls Park section of the Nashua River Greenway is just three miles from downtown Nashua, New Hampshire, but is sheltered by arbor. In the rain, the earth blends underfoot, the trees drink, the river replenishes, the world expands.

Stoddart grips a hiking pole in each hand. Her small frame swallowed by a blue raincoat, the 96-year-old tells a tale as she walks, sometimes pausing to lift a pole and point it out over the river. In the two wooded paths flanking either side of a healthy waterway, she sees a lifetime of work, hundreds of characters playing roles of all sizes in a story she wrote, but also chapters of empty pages, begging to be filled with the continuation of a vision she cultivated.

Today, hiking and canoeing along the Nashua River are two of Stoddart’s favorite activities. “It’s like being in paradise,” she said. “You wouldn’t find a more beautiful spot in Maine or Vermont than you would paddling along the Nashua River.”

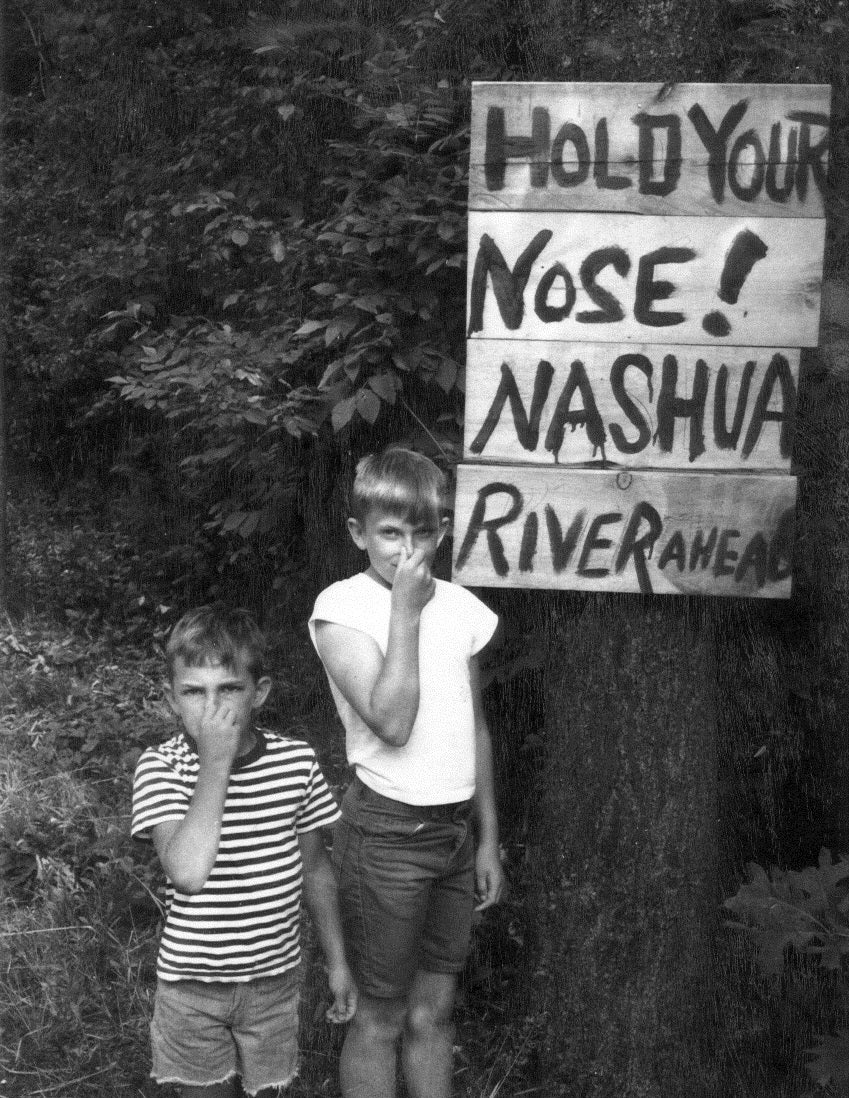

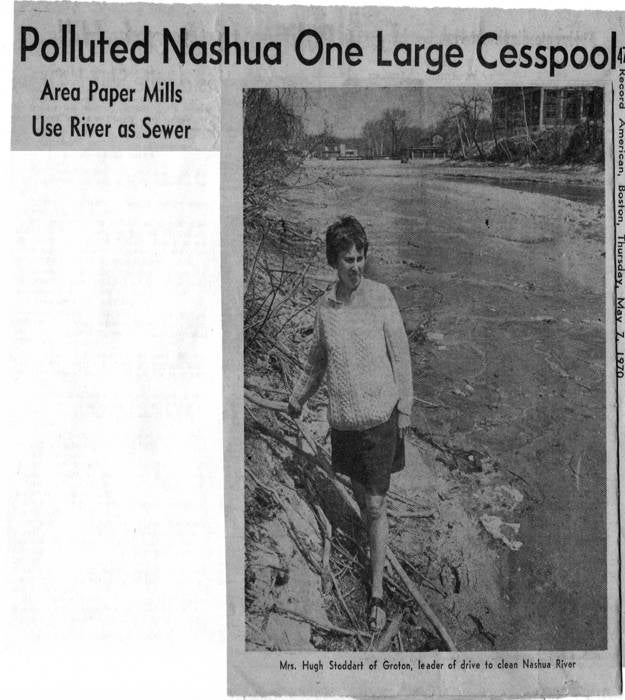

But in 1962, when Stoddart first moved to Groton, a quiet town in central Massachusetts, the opposite was true. Her home near the river was permeated by the water’s rotten-egg stench. Paper and textile corporations that lined its banks used the Nashua as a dumping ground and—with no treatment systems in place—had infected it with their waste. The Nashua River was a 56-mile wound, cutting through two states, a toxic sludge oozing where water should have run.

Taking on the challenge of a lifetime

But Stoddart saw a different future for the river. She was ambitious and politically active, well-known as a go-getter among the League of Women Voters, and was less than enamored by her husband’s declaration that he would like to live in Groton forever.

“Live here forever? … What am I going to do?” She remembers asking herself. It made her wonder what her purpose was on Earth. Nobody was coming to answer that question for her. So, she decided, “I’ll just choose the greatest challenge that I can accomplish during my lifetime, and I’ll commit to that. And I decided that I would commit to restoring the Nashua River.”

Stoddart’s plan was progressive. She dreamed of swimming and boating on the Nashua, of families congregating on its shores, and of living next to a river where the stink of sewage no longer permeated the air. But she understood the nuanced connection between land use and clean water. Her vision for the Nashua was not only to keep waste out; for it to be truly healthy, it had to exist within a connected and stable watershed. That meant protecting the land around it and its tributaries, the Squannacook and Nissitissit Rivers.

To help others envision and connect with her goal, she described a ribbon of blue flanked on both sides by green banks. The protected land lining the waterway would form the Nashua River Greenway. Greenways are connected areas of undeveloped land, set aside amidst otherwise urban landscapes that provide recreation opportunities, keep water cool for fish, support wildlife and vegetation, protect against bank erosion, filter groundwater, and sequester carbon.

Stoddart aimed high. Her goal was, and still is, to protect 100 percent of the banks along both sides of the river and its tributaries, running from the headwaters to the confluence of the Nashua with the Merrimack River. That’s over 400 miles of waterfront property crossing dozens of town and city boundaries.

Developing a river strategy beginning with land

When she began her crusade, Stoddart recognized a unique window of opportunity to protect the greenway. Riverfront plots were of little value. Nobody wanted to live near the Nashua, let alone have their lawn run up against it. If she could convince state and city stakeholders to purchase the land while the river was still polluted, it would be much simpler and cheaper than doing so after the cleanup when its shores were transformed into a desirable asset.

She approached the director of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. “I was going in … and asking—pleading— with him to buy land.” But the director was working with limited funding and was not willing to gamble with it. “He said ‘well Mrs. Stoddart if you can guarantee that the Nashua River is going to be cleaned up … in five years, then I’d be interested,” she remembers. “But of course, I couldn’t guarantee them anything.”

Other leaders delivered the same message: it was not their policy to purchase land along polluted rivers.

Changing plans, developing capacity, and staying positive

Stoddart saw that the political winds were not blowing her way. Too many people doubted the probability of the river being cleaned up for her to sell them on prescient land conservation. Though they underestimated Stoddart, these people had fair reason to question the feasibility of her cause.

In the early 1960s, the regulatory environment of Massachusetts was far from what it is today. The legal toolbox Stoddart had at her disposal for mounting a river-conservation campaign was sparse, if not entirely empty. Laws governing pollution and environmental standards were only beginning to emerge on a national level in the United States. There was the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (1948)—heavily revised in 1972 due to its failure to staunch rampant waterway pollution—and the National Air Pollution Control Act (1955), but it would be nearly a decade before President Richard Nixon signed the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA), catalyzing a wave of regulation around land, water, and air quality.

One of Stoddart’s strengths, though, was her bright outlook. “Her positivity is really what has carried her through,” said Wynne Treanor-Kvenvold, Community Programs Director for the NRWA, who has been on staff since 2000.

Some of Stoddart’s greatest early allies were other women from the League of Women Voters. Like her, that group was politically motivated and knew the ins and outs of exercising their influence on society, but it was also a tiered, national organization that moved like a barge.

To accomplish what she was aiming for, Stoddart needed a speedboat, a group that was nimble, efficient, and able to pivot quickly to take advantage of fleeting windows of opportunity. For that purpose, she formed the Nashua River Cleanup Committee (the committee)—the informal predecessor of the Nashua River Watershed Association (NRWA)—which was also women-led.

Its goal was to take the river from a class U—meaning it was considered unsuitable for the transportation of waste—to a class B, which would require regulators to ensure the river was safe for swimming, boating, fishing, and other recreational activities.

This work was herculean. Stoddart and the committee rallied the community around the river to fight the corporations that whined—what would you rather have? Clean water or your jobs?—to build national awareness for water policy and create precedent for prioritizing it. The women made phone calls and circulated petitions. They allied with local leaders. They hand-delivered bottles of polluted river water to then Massachusetts Governor John Volpe and Senator Ted Kennedy—desktop mementos for these leaders to remind them of the important work to be done.

Enduring political adversity

The women behind the river effort often did not get credit for their own work.

Ahead of a meeting with Governor Volpe, Stoddart’s husband advised her that the group’s message would be best received if it was presented by mayors and selectmen who had agreed to attend in support. He worried, and she agreed, that the governor might be less impressed by the same words coming from people he saw as housewives.

It was exactly their role as housewives that made Stoddart and her women-led team so effective. While the men were tied up in nine-to-fives, their wives had both the time and energy to fill their days with advocacy. And though it was the women leading the mayors and selectmen to the meeting, and who had rallied local press and state legislators to attend and garnered over 6,000 signatures for a petition being presented, it was the men who delivered the message to the governor that day.

The strategy worked. “What I think impressed [Governor Volpe] the most,” Stoddart remembers. “Is, he said ‘and all of you men, you busy men, you left your workday to come in today to see me?’”

“I learned a lot along the way about how to get attention and support,” said Stoddart.

Stocking the legal toolbox

The Nashua River Cleanup Committee’s advocacy influenced more than just its own watershed. The group was integral to state and federal environmental legislation that paved the way for a cleaner future across the nation. Even as the septic state of the Nashua River was peaking in the mid-1960s, the committee was championing the passage of the federal Water Quality Act of 1965, which gave states two years to develop water quality standards for interstate waters and to identify limits for pollutant loads to help achieve them.

In the next few decades, a slew of local and state legislation followed, all of which was heavily supported by the committee. In response to the federal Water Quality Act, came the Massachusetts Clean Water Act, which created a new regulatory agency for water pollution control, released $150 million in project and research funding, and implemented tax exemptions related to industrial waste treatment. This was complemented by sweeping amendments to the Federal Water Pollution Control Act, renamed the Clean Water Act in 1972; the Squannacook-Nissitissit Sanctuary Act (1975); and the Massachusetts River Protection Act (1996).

With a legal basis for her work and the emerging funding opportunities that came with the new federal attention to environmental issues, Stoddart’s group helped establish treatment plants along the river. Soon the corporations she had been dueling were competing to see who could get into compliance with new regulation quickest.

Once its waters were being treated, the river began to perk up fast. Today, the Nashua River often welcomes swimmers, boaters, and anglers, though there are still times when the NRWA advises against swimming due to high bacteria levels.

Laying the groundwork for land conservation behind the scenes

Through all this, Stoddart had not forgotten the land.

Though her team initially was unable to interest buyers who might have secured land before its jump in value, they were able to make inroads in other ways. From the start, they carefully mapped their vision of the greenway, collecting information on the land and ownership and contacting existing owners to see who might be interested in placing a conservation restriction on their property.

The committee also began to organize greenway committees. These were groups representing towns along the Nashua and its tributaries that were appointed by each municipality’s mayor and selectmen. They were composed of conservationists who could advocate for land along the river to be protected. The groups met monthly. At each convening, members would share their success stories and the group would add new conservation areas to a map of the greenway. “It really was exciting and fun to go to these meetings and to see the progress being made,” said Stoddart.

Later, the greenway committees were helped along by conservation trusts, which the NRWA pushed to establish for each community.

Stoddart visited private landowners herself to present the idea of conservation. She advocated for the land and emphasized the difference these individuals could make on a community-wide level. But she was never too pushy.

Her strategy? “It was making friends,” said Stoddart.

She taught her successors at the NRWA to always work with positive people. Treanor-Kvenvold said that part of the job is being able to gauge a person’s willingness to learn about and become involved in conservation. When a landowner is not ready to make a commitment, she said, the Association will present the opportunity without judgement and with an invitation for the landowner to reopen the conversation if they change their mind.

Toppling the first domino

The NRWA’s work behind the scenes reached a turning point in the late 1960s with the protection of Mine Falls Park. What was once a series of wastewater settling lagoons was filled in to create sports fields thanks to a $1-million project grant.

“Before [Nashua residents] had raw sewage flowing through their city,” said Marion. “It was really pretty grim.”

Stoddart and the NRWA were not directly involved in creating or cleaning Mine Falls. That initiative was led by the city mayor and staff. But some of those working on the project attended greenway committee meetings where they received moral support. “We were applauding them and encouraging them and supporting them to do what they were doing,” said Marion. And the outcomes from Mine Falls were empowering. “Their success encouraged other people to continue their work,” she said.

City leaders were pleased with the results of their investment and saw that their work could benefit their communities further if the area was equipped with trails along, and bridges across, the river.

That paved the way for the larger, 325-acre park to be created and conserved when the City of Nashua purchased the property in 1969 using a combination of city funds and a Land and Water Conservation Fund grant. In doing so, it preserved the first parcel of land along the river since the Groton Memorial Town Forest was established in 1922. Today, a trail system winds along the river, through forest, wetland, and fields, with footbridges connecting either side of the river and a boardwalk improving the accessibility of marshy areas.

After the city protected Mine Falls Park, people opened to the idea of conserving more of the greenway. In its first three decades, the Greenway grew from two miles of protected riverfront to 84 miles across New Hampshire and Massachusetts.

Creating high-visibility partnerships

In 1969 Nashua River Cleanup Committee, which previously had no official organizational designation, was getting federal attention for transforming the river. People told Stoddart its work could be used as a national model, but that it needed to present itself more formally. Reluctantly, Stoddart—who had held out on incorporating the group as a nonprofit to avoid getting weighed down by bureaucratic requirements—okayed the move. The committee became the Nashua River Watershed Association.

At this point, Stoddart and the NRWA had a diverse network of key partners in addition to various state and local political leaders. Among her most important allies were the local sportsman’s clubs. These groups were interested in keeping areas wild enough to enable fishing and hunting and, in the 1960s, many were actively promoting state legislation that would help protect land along the Squannacook and Nissitissit Rivers. Though she had no previous connections with anyone from these groups, Stoddart had her eye out for stakeholders, especially those with political weight, and was able to foster a strong working relationship with their members. “They were great allies,” she said.

Another unexpected source of support came from the United States Army in 1969.

She remembers getting a call from the man who was then the commanding officer at Fort Devens.

“His name was General John H. Cushman, and he called me … and he said ‘I’ve heard of the work that you are doing.’” Just over eight miles of the Nashua River runs through the fort. “He said, ‘What can I do to help you?’” She brought him a list and he delivered. “He gave me everything on my list and more,” she remembers. She got an office with utilities included, donated staff time from engineers, drafts people, lawyers, and a wounded hospital patient with a background working for the forest service.

“You never know where your help is going to come from,” said Stoddart.

Preparing to hand off the baton

In 2024, 200 miles (nearly 50 percent) of the riverfront is protected through a combination of mechanisms and across ownership types. There are state and local parks, federal land, areas overseen by land trusts and municipal conservation commissions, and parcels protected by individuals.

The NRWA’s work is now higher-tech and more formalized than it was in its early days. But its strategy is still very much shaped by the example Stoddart set. Treanor-Kvenvold said that staff still collect lists of landowners in target areas and bring them together for face-to-face information sessions, inviting them to continue the conversation afterward. The NRWA is unique in the region for its dual focus on both land and water resources, which reflects Stoddart’s initial plan for the watershed.

Today’s NRWA also builds on the foundation she set. Sometimes the team will return to follow up on relationships that were established a decade ago, but that were not yet ripe for commitment. “It’s all about relationships,” said Treanor-Kvenvold. “And the hope is that you can pass those relationships on as staff changes.”

Though she has been formally retired from the NRWA for years, Stoddart will still attend meetings and continues to represent the organization around town. “She’s just so convincing and so dedicated to the work that she’s always a great spokesperson for us,” said Treanor-Kvenvold. “And she also doesn’t hesitate to talk to people about her cause. That’s been true from the start.”

Her natural way of promoting her cause has had an impact beyond just recruitment. A film about her work cleaning the river called “The Work of 1000” frames what she did as being that of a thousand people, which Treanor-Kvenvold said is absolutely true, but not the whole story. “[In addition] she’s also inspired generations of people to pick up what she was doing and keep moving, and I think that’s hugely important.”

Staff join the NRWA inspired and motivated by Stoddart, ready to carry on the work that changed their community in a hugely visible way.

Connecting a new generation with land and water

Stoddart said that one of the most important resources the NRWA now offers is its River Classroom—a canoe-based program offered in collaboration with Nashoba Paddler—that brings youth out onto the river and greenway. The aim of this and other similar activities is to connect people with the land and water. Stoddart remembers a recent interaction with a young girl from Fitchburg who had just finished up the day program. “She came off the river and said, ‘this has been the best day of my entire life!’” and Stoddart thinks many of the students feel similarly.

“What we need to do,” she said. “Is to get more children and adults on the river so that they can have this wonderful experience and then see the need, advantage, and benefits of protecting all the land that we have along our streams and rivers.”

The connections that are formed when people are introduced to nature last a lifetime. Stoddart is an example of that. Earlier this year, she celebrated her 96th birthday with a canoe trip down the river. “This is the most wonderful experience for me is to paddle along the Nashua River and to see the greenway. I do this as often as I can,” she said.

Stoddart also still attends meetings with the NRWA and continues to keep her gaze set on the horizon.

“She’s an amazing person and she just never quits,” said Treanor-Kvenvold. “We’ll have success with a major project … and Marion will be eager to celebrate, but she is equally quick to remind us ‘the work is never done.’”

Have news? Share updates from your organization or country by emailing ilcn@lincolninst.edu.