Kawartha Land Trust Pioneers a New Type of Conservation Partnership in Ontario

On October 10, 2024, the Kawartha Land Trust (KLT) and its partners launched the Kawartha Resilient Lands Collaborative at a well-attended kickoff event in Peterborough, Ontario. The new Regional Conservation and Climate Partnership (RCCP) looks to bridge sectoral divides among people and organizations working in land, water, climate, and conservation. While inspired by the RCCP model prevalent in the United States, this group will intentionally structure itself differently from its predecessors.

“[We are using] conservation as the tool for a collaborative partnership that spans conservation and climate,” explained Zoë Mager, Director of the Kawartha Resilient Lands Collaborative. “But [we are] looking beyond conventional conservation as a model to support land protection and create healthy and resilient ecosystems [by] recognizing that people are such a key part of that.”

Regional Conservation Partnerships (RCPs) are a strategy for achieving large-scale conservation outcomes by connecting like-minded organizations across sectors to pool resources, plan collectively, and reach shared goals within the land- and water-management spaces. More recently, climate considerations have been added to the model as conservationists increasingly recognize how inextricable nature and climate outcomes are.

There are over 550 RCP and RCCP organizations in the United States, but only a handful are established in Canada. This is the gap that the Kawartha Resilient Lands Collaborative initiative seeks to address.

“We are in our discovery phase,” said Mager, describing the group as being a prototype in its current form. The collaborative was launched by the KLT, with help from the Centre for Land Conservation (CLC). The KLT now serves as the backbone organization for the collaborative, which it hopes will grow to become increasingly autonomous. The CLC is a national organization that has been monitoring the development of the collaborative to explore its potential to be replicated across other regions.

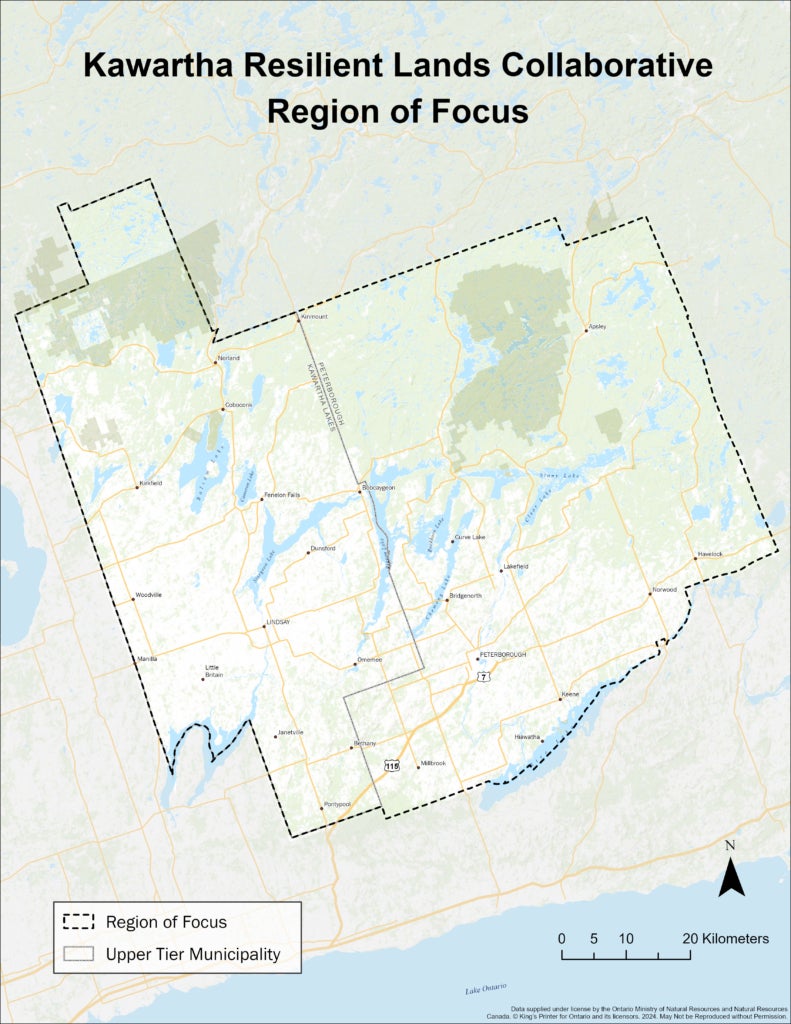

All three organizations are exploring what it means to be an RCCP in Canada, and whether that model is even aligned with the unique needs of the communities in the 1.7-million-acre (about 687,965-hectare) region the group will serve.

After much of the world signed on to the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework in 2022, KLT and CLC recognized an increasing appetite for collaboration among those working toward conservation goals in the Peterborough region. Increased partnership was integral to achieving Target 3, known ubiquitously as 30×30. It was a lack of financial and personnel capacity that hindered that collaboration.

In developing an approach to that issue, KLT and CLC looked to many existing initiatives for inspiration. In the United States, Wildlands Woodlands Farmlands & Communities, a regional conservation partnership network in New England, is a prominent example and has achieved measurable results in terms of land protected through the partnership. In Canada, several organizations practice similar work but predate the RCCP label. KLT and CLC looked to the Kootenay Conservation Program, the Thompson-Nicola Conservation Collaborative, and Corridor Appalachien as inspiring landscape-scale initiatives working in the Canadian context.

What KLT knows it wants to do differently with this collaborative is to include less-conventional partners who are working at the intersection of land, health, education, climate resilience, and industry. This was reflected in the audience of its kickoff event, which welcomed about 70 participants from 40 organizations including government officials, environmental nonprofits, First Nations leaders, educational institutions, and various industry associations, including representatives from homebuilders’ associations, agriculture, and forestry.

“We need to reach across sectors and find a way to collaborate together,” said Mager. “The hope is to go beyond the usual suspects of land conservation and recognize that people interact with land in different ways and people are impacted by land in different ways,” said Mager.

The Kawartha region, where KLT is located, lends many attributes to the success of an RCCP. Mager said that it is big enough to house organizations including the headquarters of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and a university and college with strong environmental and Indigenous programs. But it is also on the edge of “cottage country”, where many people connect to land through recreation and are eager to support local conservation initiatives. In addition, the region falls within Michi Saagiig Anishinaabeg territory, where Williams Treaty First Nations have strong, continued traditions, and practice their culture, which is inextricable from responsible land and water stewardship.

Though it is in its early stages, the collaborative is gaining momentum, fueled by a flexible funding source. The ECHO Foundation, a Montreal-based charitable foundation working at the intersection of mental health and the environment, is funding the initiative through its first three years. The group has additional support in the form of collective impact coaching from Innoweave and is in the process of applying for supplemental grants.

One challenge the RCCP faces is defining and measuring success. The leadership team is looking into other examples of valuation models for similar initiatives, including One Tam’s Partner Impact Evaluation Guide. Mager said that any model the collaborative adopts will need to consider both qualitative and quantitative outcomes and may not capture the group’s full impact.

One of the primary ways the group seeks to bolster resilience against climate change and biodiversity degradation is by enabling better partnerships between Indigenous and settler groups. “There are so many different examples that we are looking to for how to be in better relationship with people who are original stewards of the land,” said Mager. Existing relationships provide a strong opportunity to leverage and improve collaboration through the RCCP. “We have a really key role to play in that,” said Mager.

For now, involvement in the RCCP does not require any kind of formal commitment. Rather, people and organizations choose to participate as much or little as they like, ranging from simply receiving communication from the group to getting their hands dirty in strategy and organization.